The inevitability of AI has made me think about my relationship with technology a lot lately. My suspicion of it hovers prominently, but as a writer, marketing professional, and everyday consumer, I cannot possibly ignore AI’s massive impact on both my behavior and thinking. Language, the beloved material of my craft, is becoming inert data to be fed to machines that will, in turn, return them to us as surreal facsimiles with the capacity to influence our lives, positively or otherwise.

I think about this as I think about why I bought a film camera in the first place. It doesn’t make a lot of sense when the camera phone I carry with me at all times is more sophisticated in every way: higher resolution, video capabilities, unlimited storage, instant gratification and publication, a built-in editing software, access to the internet. The impulse to acquire the film camera, I admit, stemmed from a nostalgia for an era I caught only the tail-end of, and the romantic desire to make moments feel more “special” by turning to analog in a digital world.

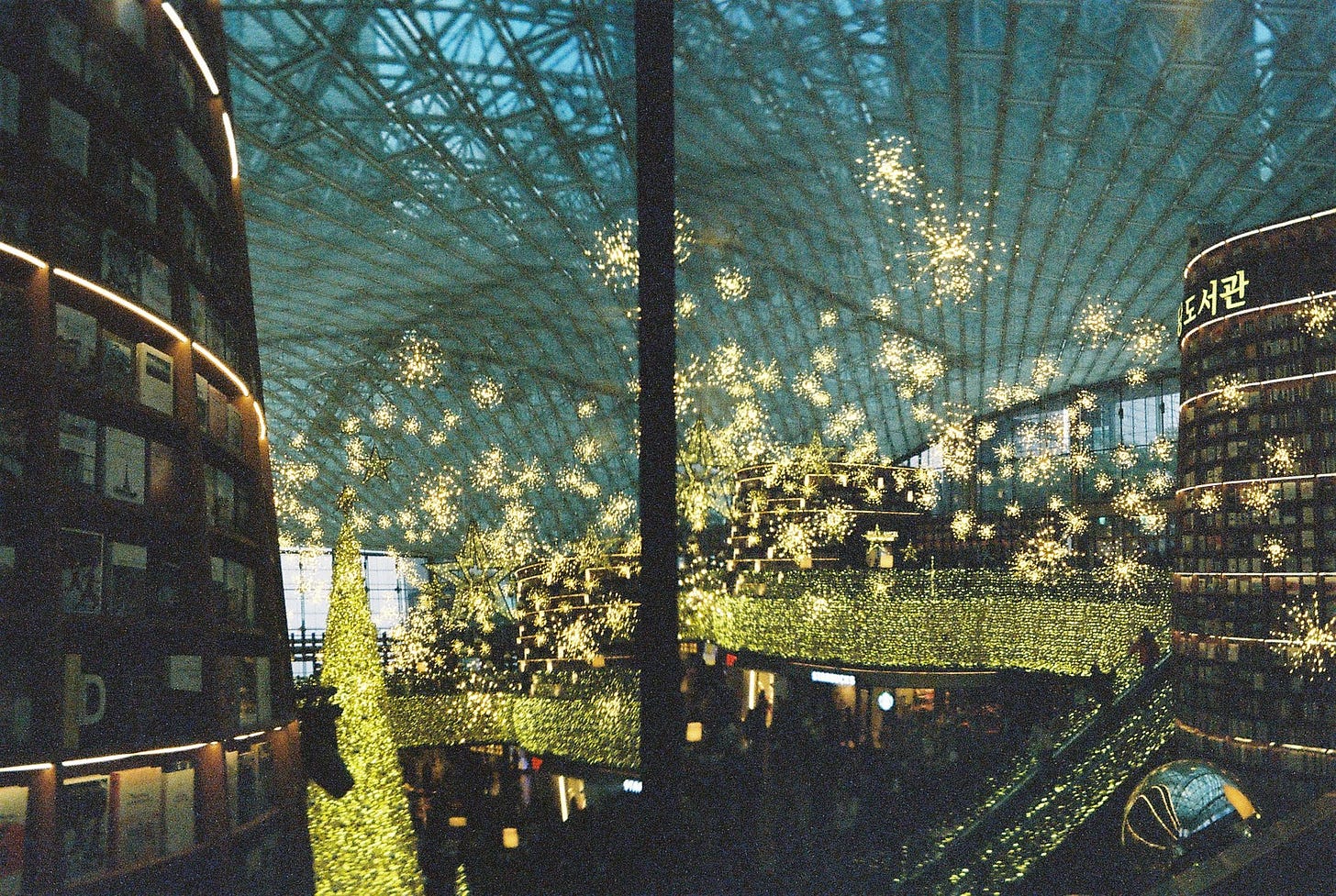

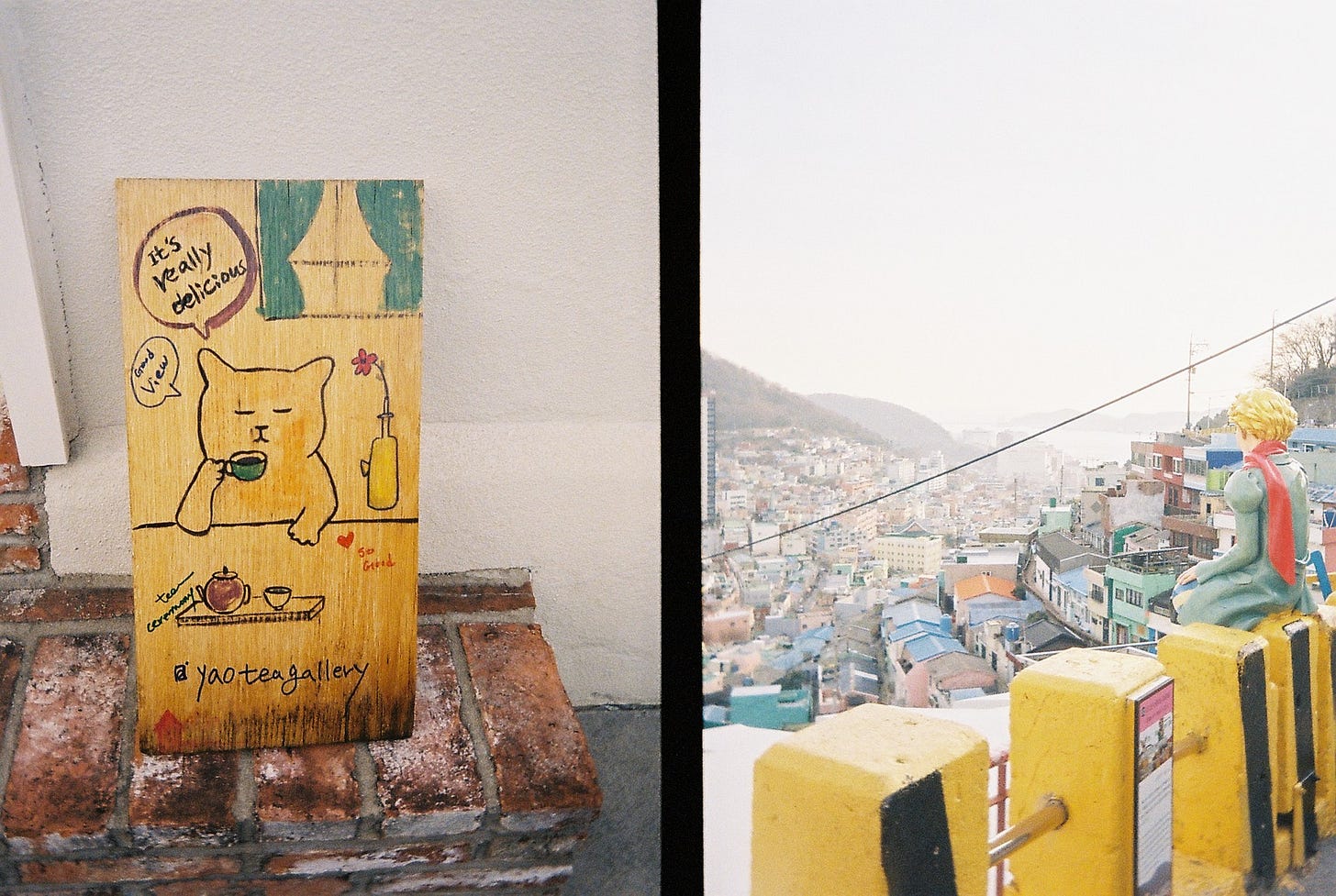

Having brought my Kodak Ektar H35 half-frame to our South Korea trip, I observed in myself several thoughts and questions that likely wouldn’t have occurred to me with another instrument:

Not knowing the outcome of a photo I just took was a thrill. With a point-and-shoot camera and little-to-no photography skills, I mostly prayed for the best with every click of the button. There was a lot of faith in the distance I chose to stand from my subject, the lighting in the room, the mechanism of my plastic camera.

That a film roll could only capture a handful of photos meant I needed to be very intentional. In a way, I was always negotiating with myself, because I had to balance the impulse to take as many photos as I can with the temperance of not taking too much. There was always a pause: Of all the interesting scenes and episodes during our trip, is this the right moment to capture? How do I want to frame my subject/s? Will I have enough film for the rest of the day?

I know that the photographed moment looked different from the photograph of the moment. The hues are a little warmer, the photo overexposed. The photos are far from reality, but, perhaps, closer to my memory. Walking Haeundae Beach with my siblings on a cold, sunny day feels less like the realistic photo on my phone and more like the bright, grainy one I took with my film camera.

I kept my phone in one pocket and my Ektar in the other. Using both digital and film cameras, journaling, and even making rough sketches of the flower vase at a café were comforting. I felt assured that I was taking every opportunity to live in the moment—rendering an experience into art requires attentive observation—while also preparing to remember it. I found the latter impulse to be a fascinating distillation of past-present-future in a single gesture.

Switching between phone and film cameras revealed how differently these media invite me to think. With the Ektar, the act of creation ends with the click of the shutter. The composition is final, so the outcome rests fully on the decisions I make at a single moment. Great photographers have honed the instincts and knowledge necessary to turn their vision into reality by working with the current conditions of the present. But with my camera phone, I could manipulate nearly every aspect of the photograph after I’ve taken it—the ratio, its color balance, its sharpness. Framing is still important, but taking digital photos exercises a different creative muscle. It requires a different kind of imagination. Access to these technologies are, by extension, access to different modes of expressing myself and encountering the world.

The tools we use change us, and reveal something about us, don’t they? Michael and I had just finished rewatching one of our favorite shows, HBO’s His Dark Materials, which is an adaptation of Phillip Pullman’s trilogy of the same title. In what is essentially an epic narrative about free will, three objects prove vital in the great war against an oppressive Authority whose regime spans the multiverse. Through them, certain characters gain access to truth, wield willpower as a weapon powerful enough to cut through worlds, and see the elementary particles of consciousness itself.

The characters’ growth and abilities—and ultimately their purpose—become inseparable from these objects, and this brings me to wonder how the technologies I use complement, encourage, or stunt my own growth. How do they help me move closer towards the person I want and need to be? What new faculties of thinking and feeling do my smartphone or analog camera enable? AI? What are the costs and are they worth it?

Muscles we don’t use atrophy, so when we outsource tasks to our tools, I do think it’s important to carefully consider what we gain and lose. I may seek AI’s help in drafting captions for the social media pages I manage for work, but I can’t imagine giving it the honor of doing the background research for an essay I’m writing. I don’t particularly cherish social media marketing skills beyond the employment opportunities they open up; however, the patience, critical thinking, discernment, and perseverance that doing my own research cultivates—I don’t want those capacities ever taken away from me.

These concerns bring me back to Martin Heidegger’s essay, “The Question on Technology”. I won’t even attempt to summarize his entire lecture, but I latched onto a few concepts to guide my own inquiry. The first is that technology is not mere means or instrument, but is a “mode of revealing. Technology comes to presence in the realm where revealing and unconcealment take place, where aletheia, truth, happens.” (Interestingly, one of the key objects in His Dark Materials is the golden compass, which is also called an alethiometer.) The second is that the roots of technology, if one traces it etymologically, is more poetic than mechanistic:

The word [technology] stems from the Greek. Technikon means that which belongs to techne. We must observe two things with respect to the meaning of this word. One is that techne is the name not only for the activities and skills of the craftsman but also for the arts of the mind and the fine arts. Techne belongs to bringing-forth, to poiesis; it is something poetic.

Following those arguments, I then think about artificial intelligence as something revelatory; as the emergence of something new (poiesis). Not in the sense that AI creates—because it doesn’t—but that in its creation, like any other revolutionary technology, something new has been revealed. New ways of thinking/feeling/being have been made possible that will irrevocably change us and the way we engage with each other and the world. These possibilities reveal a truth about who we, collectively, are becoming. What, for instance, are the implications of outsourcing human thinking to a machine? A truth stares us in the face as we ask ChatGPT how to spell “strawberry” or to write a polite, straightforward email to a recruiter or whether or not climate change is real. I can’t say I know what that truth is yet, only that it warrants serious consideration. Without it, I go into the future, built on stacks of AI technology, as just another series of data points.