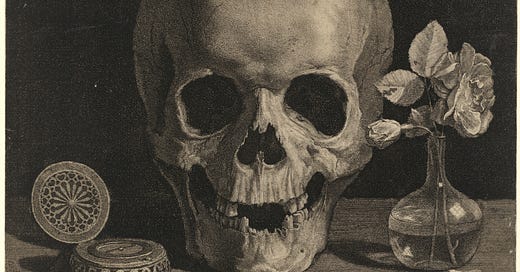

Memento mori

Notes on collective responsibility (and why the best thing we can do for the earth is to remember that we will die)

Few things horrify me more than what humans will do in pursuit of permanence or eternal life: maintaining the myth of empire, digital immortality, life-extending “healthcare”, just to name a few. (The show Altered Carbon best illustrates the horrors that will come to pass if we succeed in this endeavor.) This aspiration to never die is a dream to never return what has been given.

Natural law calls for life and death. What is asked of us is not the creation of something that lasts forever, but one that serves to continue what came before us the way it takes monarch butterflies four generations to successfully complete their migration. In lieu of immortality, I favor the humility to know when to pass the baton.

Us who presently hold this baton have the responsibility to remember where we come from as we design our present that, inevitably, shapes the future. It’s a big, necessary ask—most days I am too tired to think beyond the evening. But without this presence of mind, we lose our way, I think, even with the best of intentions. The narratives we tell ourselves can be easily corrupted. On Earth Day, I ask: Where does the impulse to live “more sustainably” come from? What do the actual practices look like? When we call for a reduction of plastic production by 2040, are we calling, too, for a reassessment of our consumption habits and dependence on convenience? Or do we really believe we can innovate our way into having it all?

How have I been failed and prepared by those who came before me? When the time comes for me to die, whose lives would I have touched? What ideas would I have helped ferry into the world? While I live, what can I do that is beautiful or liberating—essential? As I try to answer these questions I hope to find “the red thread of experience”, as Walter Benjamin calls it, that binds me to previous and future generations. “Where do you hear words from the dying that last and that pass from one generation to the next like a precious ring?”

These days, as a writer, I think often of this statement by André Breton: “The work of art is valuable only in so far as it is vibrated by the reflexes of the future.” It is impossible to tell what these future reflexes are or will be, but the clues are already here. We likely take part in making them, too. Somewhere in this nebula of artificial intelligence, cryogenics, constant surveillance, streaming services, co-opted art, televised wars, and fragile food systems are the fragments of a future I’d like to have a hand in building. I have a feeling I’ll spend all my life attempting to piece it together.

It was timely, too, that I finally made time to read Tolkien’s The Hobbit this week. I have not stopped thinking about Gandalf’s last line where the wizard complicates the idea of agency and heroism with a casual suggestion of destiny and divine providence:

Surely you don’t disbelieve the prophecies, because you had a hand in bringing them about yourself? You don’t really suppose, do you, that all your adventures and escapes were managed by mere luck, just for your sole benefit? You are a very fine person, Mr. Baggins, and I am very fond of you; but you are only quite a little fellow in a wide world after all!

As another little fellow, I echo Bilbo’s relief—“Thank goodness!”—while aspiring for the same courage and clarity of purpose even in the face of monsters. And, of course, knowing when the time has come to pass on the Ring.

Death is underrated. What you wrote is a great reminder of my own mortality, thank you. Caitlin Doughty (Ask A Mortician on YT) talks a lot about rituals and beliefs, maybe you’d find her and her organization interesting.

What we do with our body after we die has been in my attention recently almost as much as what we to it while we are alive. Thank you Lian for this piece.