Last Sunday, my grandmother-in-law Victoria and I went to a baguette-making class hosted by the Barton Springs Mill in Dripping Springs. My breadmaking experience is limited to the two loaves of sourdough I baked last month so I was partly nervous and mostly excited as I made the scenic drive to the venue.

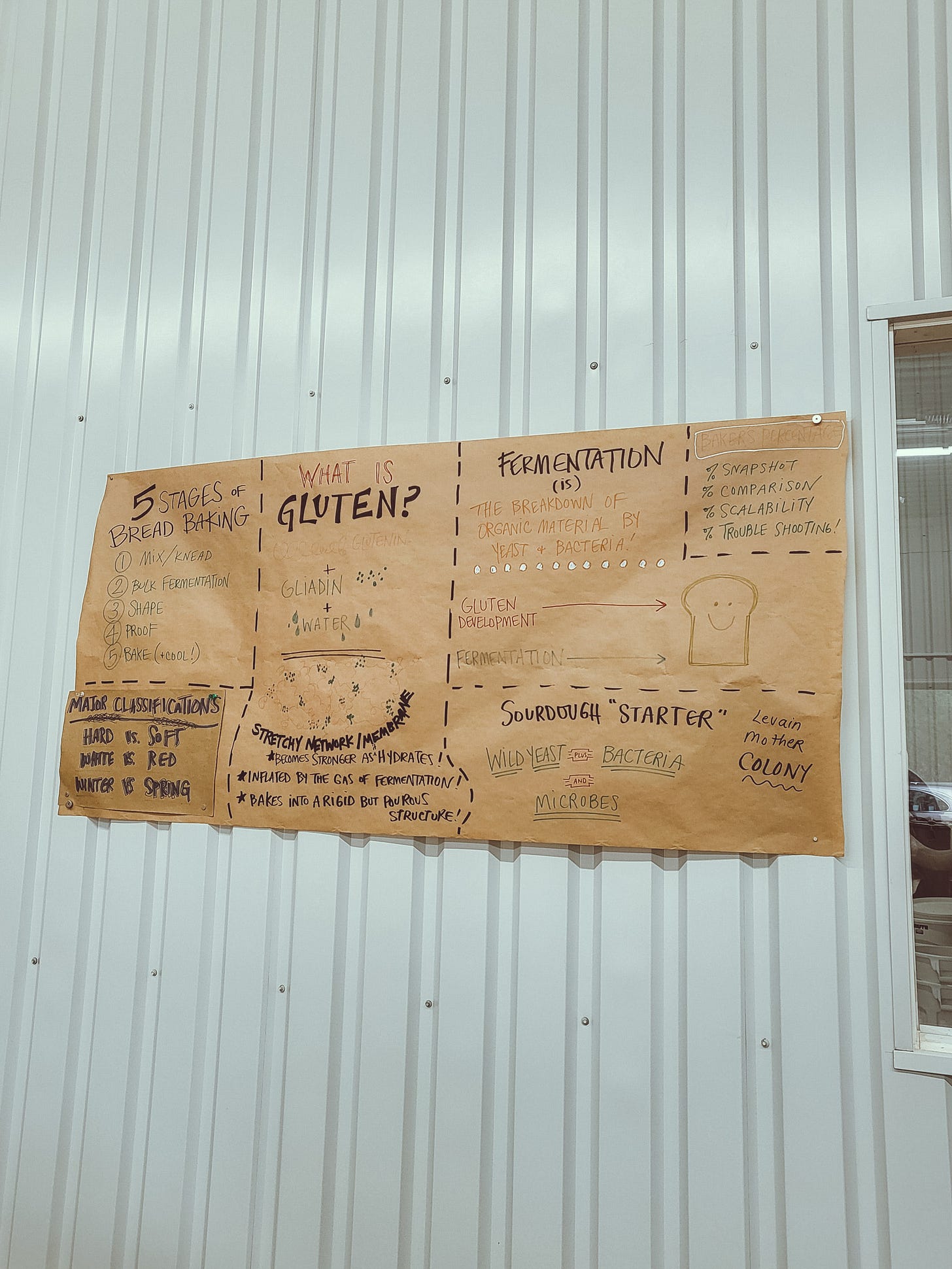

When we arrived, the classroom—clean, spacious, and brightly-lit—was already prepared with everything we needed for the class. At each station was a bowl of flour covered in cloth; another with the starter and water, combined but unmixed; pinch bowls with pre-measured salt and dry yeast; a plastic bowl scraper and metal bench knife, and; a printed copy of the day’s baguette recipe. On the wall was a charming breadmaking FAQ handwritten on sheets of kraft paper.

The workshop teacher, Tyler Carpenter, led the class with effortless knowledge and humor. His expertise was obvious—you could see it in the way he handled the dough at various stages, the way he struggled to explain what was, to him, muscle memory. His co-teacher Harmony took over in translating that instinctive know-how into easy-to-follow steps. Some of the most valuable lessons from the class include: tips to recognize indications that a dough is sufficiently kneaded; the proper technique to shape a baguette; the basic principles of baker’s math, and; understanding the differences between flours to achieve one’s desired texture and taste. For the baguette, we were provided with a mix of Yecora Rojo, a hard red wheat, Sonora, a soft white that lends the fluffiness, and Wrens Abruzzi, a light rye with a subtle, honey-sweet flavor.

Most of the four-hour class was actually rest period for the dough, so the facilitators took that time to tour us around the mill, serve an excellent selection of snacks, and answer questions from both the expert and novice home bakers in the class.

One issue I’ve encountered in my last two sourdoughs was a scorched bottom and an insufficiently browned crust, likely due to the proximity of the dutch oven to the heat source at the bottom of my tiny oven. I asked Tyler if there was a trick to avoid that. His answer, as someone who used to live in an Airstream, was simple: “It is nearly impossible.” To achieve the crust without burning the bottom of the loaf, sufficient distance from the heat source is non-negotiable, and this is just not possible in my current setup. I will have to settle for not-so-pretty but still delicious homemade bread.

By 2 o’clock, sweet, malty aromas swirled the air as the loaves baked in the steam-injecting commercial ovens at the front of the room. I watched the timer impatiently, eager to see my work and, later, bite into a slice of it, still warm from the baking. We all were moving around the space while waiting, nibbling on the leftover breads and cheeses, perusing the merchandise at the back, chatting with our neighbors and showing pictures of each other’s last bake. By the end, each student took home two footlong baguettes, one scored by Tyler, and the other scored by us. It was excellent.

Rice was our household staple growing up, and despite my parents running a bakery for a few years, we rarely had bread at home (or maybe I ignored it). When we did have bags of fresh bread—a loaf of soft tasty, some pan de coco or Spanish bread—I would pay them no mind unless there were no other options. The funny logic of my body refused to accept bread as a proper meal or a satisfying midday snack, preferring always a cup of rice for lunch, or instant noodles when I am hungry a few hours before dinner.

While bread has never been a favorite, a visceral dislike for it developed during my first visit to London in 2015. Breakfasts at the inn my mother, sister, and I stayed at were essentially a long table filled with trays of sliced bread, either white or whole-wheat, a modest assortment of pastries, some jams, packets of butter, and two conveyor toasters. Unless it was a proper restaurant, the cafes and eateries we found ourselves in served mostly bland, white bread sandwiches or something with beans. By the third morning, at a diner near Camden Town, I had gotten so tired of the food that I started quietly sobbing in front of my plate of eggs benedict. The runny hollandaise sauce held no appeal as I imagined a plate of beef tapa with still steaming garlic rice in the shape of a flower spinning under a spotlight. Our waiter kept asking what was wrong, but I said it was nothing, everything is fine; it was hard to explain. After that, we mostly ate in Chinatown, often ordering enough to have leftovers for the next meal or two. I did not eat bread for months upon coming back to the Philippines.

Eight years and plenty of breads and pastries later, the disdain had faded to indifference. I no longer disliked bread, but it was still very low on my food preference list. Appreciating the nutritional value of multigrain bread, which is what Michael and I regularly buy, was the main reason I consumed it. A slice of this bread is a valuable source of fiber and energy that I can eat in the morning with little effort—food as sustenance with little pleasure.

Sourdough, however, has wholly converted me. My interest was piqued late last year upon finishing Michael Pollan’s Cooked: A Natural History of Transformation. He dedicates one chapter to understanding breadmaking, the culture and history around it, as well as the mystery that makes bread possible: fermentation. I hadn’t appreciated bread from that perspective before. Like many of my favorite foods—kimchi, yogurt, kefir, kombucha, cheese, wine—bread is the result of microorganisms interacting with otherwise plain ingredients to create something so fragrant and nourishing all at once. The beauty of controlled decay.

Despite the theoretical interest and the many sourdough-making Instagram accounts I followed, I had been too intimidated to actually start baking. The sourdough recipe Pollan shared at the end of the book was pages long, full of strange terms like levain and autolyse, and, including the time it takes to prepare a starter, required a total duration of almost a week—just to yield a single loaf!

Victoria starting her own baking journey last December was the catalyst I needed. A budding home baker herself, she generously shared what she knew, starting with having me occasionally assist with her loaves before eventually baking my own. Admittedly, she did the heavy lifting of creating a healthy starter from scratch—I was the lucky beneficiary. Once I had my own starter, a mason jar fragrant with thriving wild yeasts and bacteria, I had fallen in love.

Whether freshly baked or just reheated in a toaster, the smell of sourdough now makes me salivate. Now, there is always bread in the house, ideally homemade, as long as the hours permit. When my starter is active, the thought of feeding them, my hungry, bubbly, sweet & sour microbes, gets me up in the morning. Learning how to determine the condition of the starter by its smell and appearance is a skill I am excitedly cultivating. On weekends, I would schedule my day around my baking—yes, I can still go to the gym in the morning, but I need to be back by 8 to start the autolyse so I’ll have enough time for bulk fermentation throughout the day and have the dough ready for baking the morning after.

As I write this, Michael and I have less than half of the second baguette left, which means I’ll have to take out my starter from the fridge and refresh it for a day or two in preparation for another batch. I am eager to hold dough—sticky, stretchy, full of life—in my hands again.

Nice that you are enjoying making and eating bread Lian. Michael sort of grew up on homemade bread but it was not sourdough and for quite a while we used a bread maker. His bread eating has been upgraded. I am so happy you are so enjoying your life there.