Living in language

Tracing and honoring my literary influences this week, featuring Carl Phillips, Mina Loy, and Charles Baudelaire

A trained ambition for excellence, that occasionally doubles as misplaced perfectionism, has taught me how to be good even in things I don’t like. I am only realizing now that this is an uncommon skill—the ability to sit with the discomfort and drag my feet through the mud, smiling through the bubbling bitterness of going against myself, against my own wants and instincts. I have acquired knowledge I didn’t ever expect to have this way, by simply pushing through the process I am currently in. This learned perseverance is valuable; it is the foundation of a strong will. It is, in retrospect, what made me an excellent student. Show me the metrics, whatever they are, and I’ll ace them all. However, beyond a certain threshold, mere perseverance can be detrimental. It can blind one to the perspective and intention that give that perseverance meaning. Without these, perseverance is mindless action that inevitably leads to a numbness, a kind of misery.

Because I have been so good at developing passable competence at anything, I have compromised my ability to discern which of these skills and pursuits I actually wish to further. Numb to my own desires, I have been easily swayed by whatever current catches in my sails. In the last five years alone, I have wanted to become many different things, and actually began going down the path to each one before, like a magpie, turning my attention to the newest shiny thing. Eventually, the once tolerable wandering had made me very unhappy; the bitterness coalesced into rage. I had to choose.

Choosing meant throwing myself into a new world in which, I sensed, I would be free of the fog. In this new world, the instincts I’ve locked in the spare room would have to be let out and allowed to stretch their legs and walk me through. Farewell, Seven of Cups; hello, Fool. So, I chose to stay with my partner in the United States where, aside from him, I had little to no personal ties. It worked; without the safety nets of the familiar, I had no choice but to practice trusting myself. While I still can’t definitively say what I want to be long-term, I at least have started listening to myself again. On that I place my faith.

I don’t look back at my indecisiveness with regret. At least, not anymore; there was a period when I despaired at the time I lost by being lost, time that I could have spent building the foundation of what could be my life’s work, even though I clearly did not know what that was yet. Almost inevitably, I compared myself (and occasionally still do) to peers my age who, thanks to a combination of commitment and clarity, have made concrete progress towards becoming who, professionally, they want to be. They have passed the bar, gotten into graduate school, climbed several rungs of the corporate ladder, begun teaching at university.

Meanwhile, I feel like I have been going in circles. The one thing that has made me feel safe through it all was writing. I write because I must. Writing seems to be a condition of my existence that resists neglect. It does not necessarily follow that I pursue a career in writing—though I think about that more and more lately—only that I must keep practicing it, privately or otherwise. Towards this desire is this comforting notion, one that I’ve long carried but had been unable to articulate, by Carl Phillips: “As long as I am living in language, as I like to put it, I count it as writing.” I begin here, observing.'

On living in language: what I am currently reading

These are the sounds and images I am surrounding myself with this week—

My Trade is Mystery by Carl Phillips

My earlier reflections on perseverance were inspired by “Stamina”, the second meditation in Phillips’ collection of essays. He writes, “Maybe the best way to think of stamina is as a fusion of perspective and will.”

While I have marked many passages in the collection, I have little to say about this lovely book except that, as someone still figuring out the shape of her writing practice, I am happy to have it with me. Phillips has the most soothing writing voice I’ve ever read, so reading My Trade is Mystery felt like a guided meditation indeed.

The Lost Lunar Baedeker by Mina Loy

Presently, I recognize that modernist writers have the greatest influence on my work. I return often to T.S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land” for its surrender and ambition, to Chika Sagawa’s insistent dream logic, to the music of Virginia Woolf’s prose. What draws me in the most is the synesthetic quality of their works, the exercise of multiple kinds of logic that venture far beyond the rational. It resembles how my mind, shaped greatly by the high-speed existence of growing up in both Manila and the placeless internet, is constantly drawing and redrawing links between the disparate ideas and sensations I am witnessing. I have had the privilege and affliction of skimming through multiple languages, rhythms, idioms, cultural norms like they were flash cards. In lieu of depth, I have an odd breadth of knowledge that makes me a terrible specialist.

While researching for a new project, I came across Mina Loy, another poet associated with the modernist movement in the United States (though, like, Denise Levertov, another poet I deeply admire, she was born in the United Kingdom). I was bewildered that I had never read about her before. One pass at “Lunar Baedeker” and I was stunned—as Roger Conover writes in his introduction to The Lost Lunar Baedeker:

Once discovered, if her poems do not immediately repel, they possess. Her work is far more likely to be a toxic or a tonic—quickly sworn off or gradually acquired as a lifelong habit—than a passing interest.

Allusive but self-contained, “Lunar Baedeker” had, to me, a sense of the epic in its sound and imagery, partly from the use of relatively obscure or uncommon vocabulary, but also from what can only be a visionary intellect. From her I wanted to learn—with excitement at finding another modernist writer with less masculine sensibilities—so I dove headfirst into her collected works and, as Conover boldly claimed, was possessed.

I was also attracted to Loy for another reason. Aside from the merit of the work, Loy herself reads like a myth. She was beautiful, a trait that unfortunately or otherwise, almost inevitably elevates a woman’s social standing. It seems that people were intrigued and repelled by her, by the boldness with which she carried her charm and talents. She wrote, acted, painted, made lampshades, modeled, and patented inventions. In her writing, she often made fun of critics and past lovers. “She genuflected to no one,” says Conover.

She also seemed to elude categorization, which is likely a factor in her exclusion from the canon despite her work obviously possessing an enduring quality that, if not praise, is at least worthy of study. I liked this particularly about her: “Feminist and Futurist, wife and lover, militant and pacifist, actress and model, Christian Scientist and nurse, she was the binarian’s nightmare.” While I don’t necessarily admire everything she’s done and written—I read her “Feminist Manifesto” with pursed lips and a furrowed brow—I find much in her work that challenges me and what I think I know about poetry. For that, I wish to sit with her for a while.

Violet Energy Ingots by Hoa Nguyen

I had read only one or two poems by Hoa Nguyen when I saw that she was this year’s judge for the Tomaž Šalamun Prize. Recognizing the subjectivity of literary prizes, I figured that her selection of my chapbook meant that she not only saw an “objective” merit in my work, but also felt a resonance with it that was unique to her as the judge and reader. A different judge evaluating the exact same set of submissions may have chosen another manuscript entirely.

The honor felt like an opportunity, too, for a conversation. By that, I mean that I wanted to read more of her work and meet what she has to say. From there, trace similarities and identify differences, see where our ideas and experiences agree and diverge.

Violet Energy Ingots is a collection of poems full of potential energy. Each poem is terse and “quiet” even when it talks about rage or a kind of violence, as in “Haunted Sonnet”:

Because of that, I think she is a bit of a “difficult” read—the precision with which each word seems to be placed on the page tells me she is probably trying to say about five different things at once and I am only seeing one, if at all. Which is exciting.

I think I am the opposite; instead of being precise, I have a tendency to sprawl and sing carelessly. I haven’t decided if my inability to distill my thoughts more clearly is evidence of a lack of discipline or simply a personal disposition I should learn to accept. Either way, examining Nguyen’s style closely has been a lovely exercise.

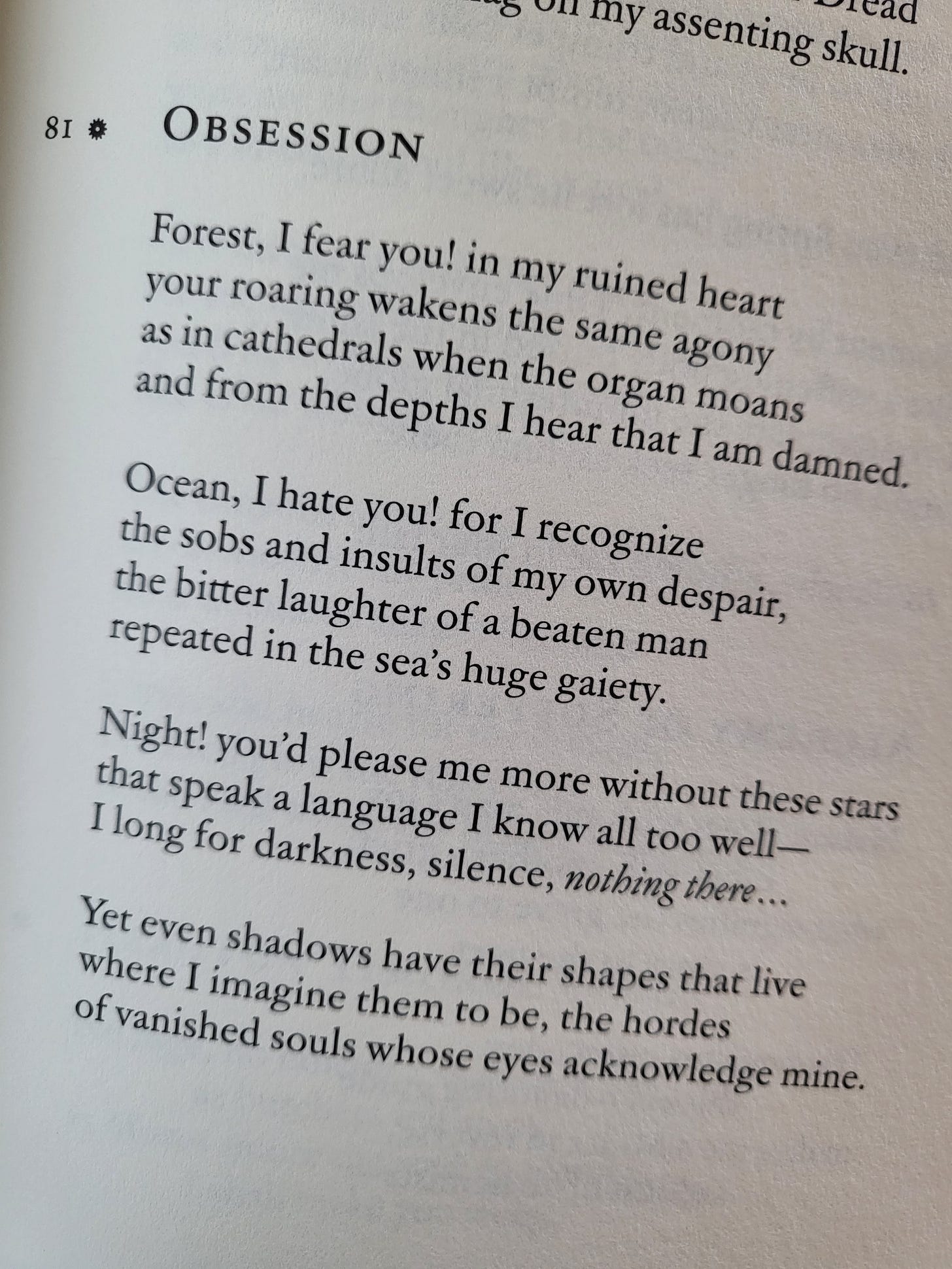

The Flowers of Evil by Charles Baudelaire (trans. Richard Howard)

There are plenty of writers I did not appreciate on my first encounter with their work. Often, these would be the literary giants that the snobbier, well-read crowd would look down on you for not having read, so this was, for a time, a source of embarrassment for me.

Thanks to massive improvements in self-esteem, I now don’t really care what people of think of me based on trivial things like things I’ve read or not read. Interestingly, I think the lifting of this psychological barrier allowed me to finally have an honest relationship with literature. In revisiting some of these authors, by chance or otherwise, I would perceive their work in a completely different light.

Baudelaire was one of those authors. When I first read The Flowers of Evil back in college—I can’t remember whose translation, though—I found him dramatic without the gravitas that gives drama its wholeness, its impact. Maybe it was the translation, or maybe I just wasn’t at a place where I could understand what he was talking about. Regardless, now I see clearly what made The Flowers of Evil a monumental piece of literature. The vivid acquaintance with darkness, told in masterful meter, is not an easy feat.

“Epigenesis” by Erin Marie Lynch on The Adroit Journal

I am trying to make a habit, too, of reading more poetry journals. Many of the writers I turn to are not from this century, which isn’t a fault at all, but I think I would benefit from hearing how other living poets are making sense of today, as I am.

This poem by Erin Marie Lynch, for instance, is a lucid examination of grief entangled with trauma. Here, personal history refracts the larger historical context it is inevitably woven into and reveals something new. More than any other generation, the one I belong to is equipped with the vocabulary to understand and unravel trauma, large or small, that had long been unnamed. I see that impulse here; I have it too. On a certain day, this is the kind of poem that would make me cry.

“No Wild Iris” by Christian Jil Benitez on eTropic

Through Benitez I understood myself better. His 10-page poem, “set” in the lockdown years of the Philippines, ruminates on the nature of Philippine time which he describes as a “disjuncture: multiplicities that insist on a singularity, or a singularity that insists on being multiple.” This is what I mean when I talk about the “high-speed existence” of living in Manila; the sense that everything happens so much all at once, all the time, and we are always so tired but we cannot stop.

Reading the poem made me sad, angry, amused, jealous, frustrated, embarrassed, cold; by the end I just let out a tired sigh. Tired, but unstoppable; “& we suffered / still; we’re making it through”. This poem is easily one of my favorites. Please read it.

“Song For My Grandchildren” by Hope Jordan on Hole in the Head Review

While there seem to be very real signs of some sort of apocalypse, I think we humans have a tendency to anticipate our demise. Every generation has its the-world-is-going-to-end crisis, and by all means, ours may finally be the one to render us extinct. I cannot say. I can only say that, like Hope Jordan in this beautiful poem, I mourn many losses and feel worried about what’s ahead, and I wish to share what I’ve learned with those who will come after me.

The virtue for the month of June is Perseverance. “ Perseverance becomes faithfulness. Its opposite is loss of grip, giving up. “