A year in vignettes: part one

How I spent New Year's Eve, reflections on certain reading habits, and eating desserts in New Orleans

This entry began as a numbered list of the few books I read last year. As I recalled them, the entry slowly evolved into a remembrance of certain episodes anchored in some of the books I read, so I embraced the impulse and wrote them down. 2022 was an eventful year for me—a turning point—and these are some of my favorite memories.

I.

For twenty-four years, I celebrated New Year’s Eve in the house I grew up in. Our tradition was to wear red for good luck, avoid serving any dish with chicken or other poultry, and watch the fireworks for a few minutes before retreating into the house for another serving of leche flan. We would organize chaotic, competitive games—Pinoy Henyo is a must—that always result in laughter, screaming, and someone overjoyed at winning the biggest prize of the night.

This year, having moved to Central Texas, I waited for midnight at one of the few bars in the small town I now live in. Entering a bar alone is always intimidating, but it is especially uncomfortable when the room is overflowing with people, which was the case that evening. All the tables were occupied by families and groups of friends wearing shiny new year paraphernalia while I came in carrying a notebook and the naïve assumption that there would be quiet space to write. On the contrary, the atmosphere was warm and festive despite the crowd of mostly dark colored tops and jackets. I was wearing a gray shirt with a javelina print and the word Marfa in red, a pair of jeans, and cowgirl boots. After ordering—a negroni sbagliato for a festive spin on my go-to drink—I parked myself at a corner of the bar and waited for a seat to open up, which, thankfully, did not take long. It is easier to be awkward while seated.

I had been to that bar a couple of times before, so the owners and I were acquainted. Like me, they came from the city—they from Houston and I from Manila. We exchanged friendly small talk here and there, but it was a very busy night so I mostly observed the scene. The crowd, aside from two families, was composed primarily of late millennials many of whom, I learned, drove in from out of town. When I got my glass, I asked Garrett to immediately close my tab as I intended to enjoy just one cocktail the entire night, but I quickly changed my mind and splurged on a glass each of their NYE specials: a Ruppert Leroy 2019 Fosse-Grely Champagne (a little too much like apple cider for my taste), and Champagne Hure Freres Invitation Brut (classic, nicely balanced).

I was fully expecting the evening to end unremarkably, but half an hour before midnight, the seat to my left was occupied by a man who, like me, came alone. As soon as he arrived, he greeted the owners, who seemed to be his good friends, and narrated how he almost didn’t want to get up from bed to spend New Year’s Eve there as he had promised. Not long after, we were introduced and quickly fell into an engaging chat. Having common ground made the interaction nice and easy. We were both writers in the same town who joked about graduating with “useless degrees”, and we both had experience with living on wheels. Brief histories were shared—living situation, origins, relationships—and somewhere in the conversation was an exchange of book recommendations, so I gave him R.F. Kuang’s Babel, or the Necessity of Violence, and he suggested the sci-fi classic Hyperion. There was a countdown to midnight, then loud whooping throughout the room, then, between us, a goodbye with a promise to keep in touch. “Welcome to Johnson City!” I was glad I didn’t stay home.

II.

When it comes to my identity as a writer, I like to think of myself as a poet, but my reading list of late has been dominated by fiction and essays. Reading poetry exhausts me in the most wonderful way, like going for a run in sunny, 60-degree weather, so it often requires me to be in a certain headspace that I cannot force my way into. Following the metaphor, some might say that it’s a matter of discipline, and it is, which is why I am satisfied with my choice not to become a professional runner or academic. When I force myself to read poetry, the words appear inert as stones on the page, like I have forgotten how to read.

I have tried to be a more aggressive reader, but my temperament with books seems to be that of a romantic lover: I savor the time spent, dedicate songs in blind worship, rave annoyingly to my friends, mourn the eventual lovely and terrible separation.

When I find poetry I like, though, I read them for a long time, and over and over again. T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land celebrated its hundredth year last December, and I still read it every few months. Sometimes, when I want to experience its musicality without much thinking, I listen to Alec Guinness’ reading of the poem on YouTube while washing dishes after dinner. Chika Sagawa, who I am able to read through Sawako Nakayasu, still reveals new landscapes to me with every reread, like an ever-changing dream setting I’ve been to on multiple nights. Reading Denise Levertov, who I discovered only recently, has a similar effect, but with her it’s more obvious that I am the one changing. I imagine reading “Seeing For A Moment” later in my life and coming to the poem with a recognition that only comes with time; with experience.

Being in my mid-twenties feels like being a teenager with much higher stakes. The false sense of invulnerability that comes with youth is newly entangled with the humility of knowing I know very little, so I often find myself vacillating between multiple discordant states. I desire privacy but crave the opportunities available to the visible, condemn current exploitative, profit-driven systems but envy those it favors, dream of changing the world but wish to withdraw from it. I want to be everything, everywhere, all at once, but, oh, there are very few things I like better than languidly folding freshly laundered sheets.

As a reader, this has translated into a resistance against poetry that is clever or perfectly contained. Beautiful, textual artifacts. I admire the craftsmanship of such poems, the delicately constructed bridge towards an aha!, but lately I have been in the mood for mystery rather than epiphany. When browsing new poetry, I am drawn to those that skirt around rather than gesture towards, usually through unexpected syntax or imagery in which I find refraction. In the past, I understood this as an affinity for the oceanic, the symbolically disruptive—l’écriture féminine. These days, I am less convinced by such an essentialist concept, although evasive, non-linear writing, “feminine” or not, continues to intrigue me. For instance: In a conversation with Rae Armantrout, Lyn Hejinian remarked that oceanic tendencies “seem the result of very poor observation”. I found that interesting, as oceanic is one way I would have described Language poetry, especially Hejinian’s, which in my opinion is far from “poor observation”. Naturally, it also prompted a reevaluation of why I read and write the way I do—do I observe poorly? Am I somehow justifying an intellectual laziness with fragmentary poetics? Or do we have different ideas of the ocean?

In the same conversation, Armantrout argues, contrary to the French feminists, that this oceanic, polyvalent style is less a feminist mode and more a modernist sensibility, one that corresponds “with conflicts in the modern and postmodern world [that reflect] an uneasy relation between part and whole”.

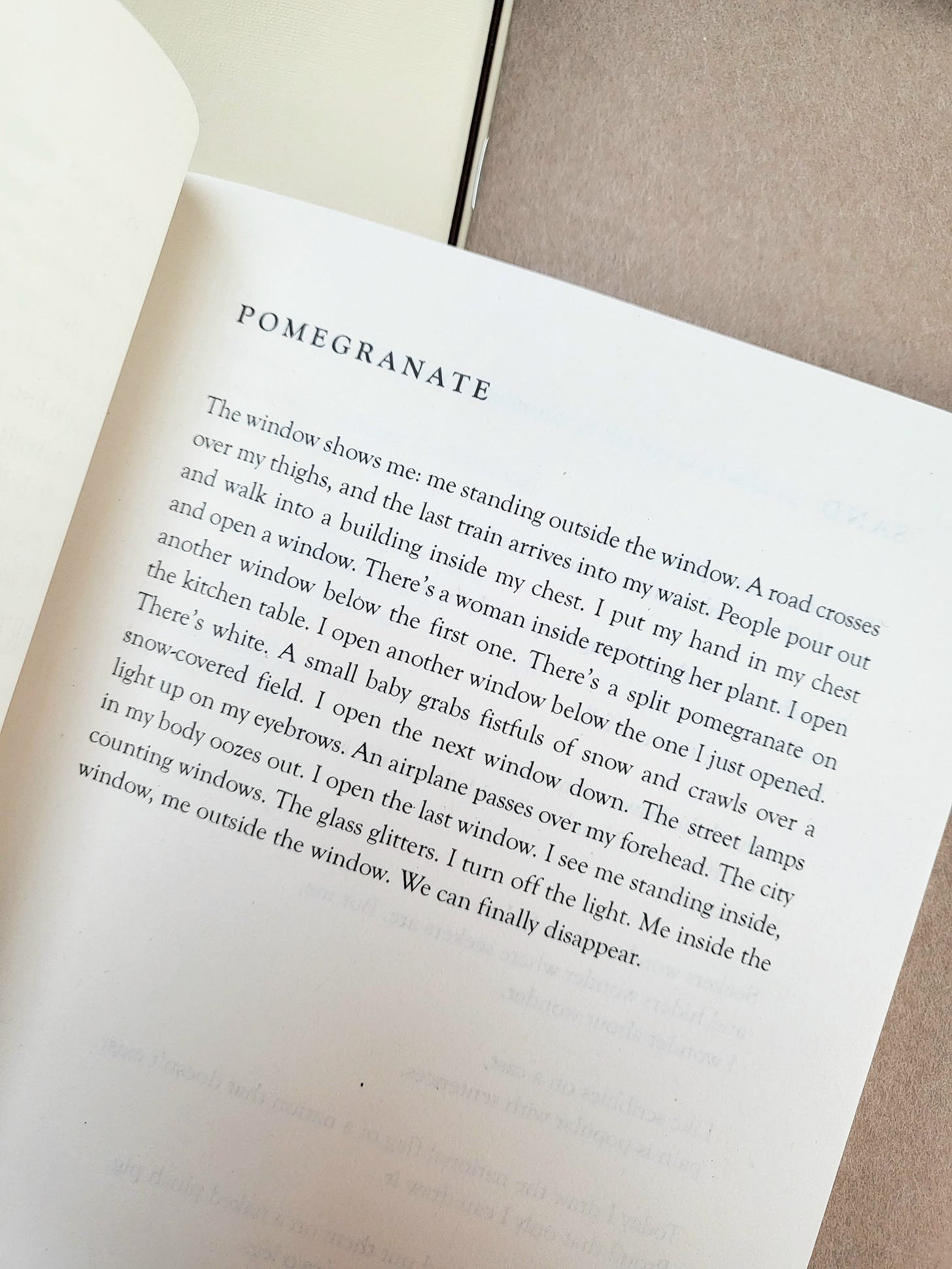

I recognized this uneasy relation in I Am A Wound Shrouded in Devotion by Zeny May Recidoro, a writer and artist I am lucky to know as a friend. In the book, inner worlds are fractured from the traumas of modern life: estrangement from the spirit, inter/intrapersonal alienation, rituals of artifice. The result is a collection of poems, vignettes, and hybrid texts that resemble the fragmented lived experience of, I imagine, many of us who live in urban or suburban spaces today, exposing from it something surreal. It certainly feels familiar to me.

Lim Solah’s Grotesque Weather And Good People is of a similar pulse, though her response to the dissonance is, with the eyes of a calm I, to turn an object or scene inside out with precise, incisive observation. As in I Am A Wound Shrouded in Devotion, there is humor, horror, tenderness. Both books renewed in me a sense of wonder in the mundane.

These are some of the texts that kept me company last year as I navigated a turbulent phase of my life. There has been much joy, but waves of loneliness, loss, and loathing continue to come and go as I build a new life in a strange place far from everything I have known. Choosing to stay in Texas was an act of love and bravery; reason, which valued security and the familiar, advised against it. This is where the folly and strength of being a 25-year-old comes in as I pursue, bearing only pure faith, the path of upheaval where illusions and entire belief systems are challenged. Here, I don’t know where I’m going, or if there is even anywhere to go, but in making the choices I did, I at least know myself better. Being lost scares me a little less.

For now, I take comfort where I can: In peaceful solitude, in meals that remind me of home, and in slippery, calculated texts that elude not out of uncertainty but out of curiosity, like being in a sprawling flower field for the first time and observing its colors on pure instinct. This is how I wish to be in the coming months.

III.

When traveling, I like to balance preparedness and spontaneity. There would be a list of eateries compiled beforehand, but where I will end up dining is a matter of proximity, cravings, and schedule. Before leaving my hotel or Airbnb, whether to walk or commute, I would look at the map to orient myself, memorizing the streets around my temporary home and visualizing possible paths for the day. Every day I would create an itinerary of my must-visits, but there would be plenty of vacant time blocks for side quests and the possibility of surprise along the way.

Another part of my journey is to read a book by a local author, contemporary or otherwise, around the time of my travels. I like to think that it helps me perceive a place without the supersaturated lens of a tourist through which everything is so unreal it must be photographed or consumed. No, I don’t mean to say that I seek to “live in the moment” or chase “authentic” experiences, only that tourists are bombarded with bite-sized, commodified heritage and I really don’t like being peddled anything. I am easily fooled.

Last October, I visited New Orleans for the first time with my family. I did not know much about the city, much less the state of Louisiana, beyond certain words: Mardi Gras, Katrina, the American South, Creole cuisine. The humidity in the colorful, sinking city was a familiar and heavy companion during my walk to Faulkner House Books along Pirate Alley, which flanked one side of the famous St. Louis Cathedral. There, I picked up two books: Kate Chopin’s The Awakening and Unfathomable City: A New Orleans Atlas, edited by Rebecca Solnit and Rebecca Snedeker.

The latter is part of Solnit’s atlas trilogy with the University of California Press, which also features the country’s two other cultural capitals, San Francisco and New York City. This reinvention of the atlas, one composed of essays and maps that go beyond topography and train lines, presents a rich slice of a place possible only through the overlapping imaginings of natives, seduced newcomers, and returning devotees. Unfathomable City navigates the Big Easy’s evolving quirks and contradictions: its celebratory, festive spirit alongside a history of violence, its cultural diversity and deep racial divides, its infinite hold on the American imagination vis-à-vis its unstable ecological future. With only four days in New Orleans, I barely went beyond the French Quarter, the world-famous neighborhood dense with life—a dizzying selection of restaurants and take-home food products, kitschy souvenirs, street music on almost every other block, tarot readings, small exhibits in historic buildings—but reading the book made me feel like I had seen so much more. The farthest my family and I traveled from our accommodations was the Audubon Park. Taking the Saint Charles Streetcar Line, we disembarked at the Tulane/Loyola stop, cooled down with a sno-ball off a truck, and walked the entire length of the park in the middle of a sticky summer day. Upon reaching Magazine Street at the other end, sweaty and light-headed from the heat despite the abundant shade from ancient oak trees, we concurred that the next destination should be ice cream. We rode an Uber to Sucré, a renowned dessert emporium that, after a sudden closure associated with the previous owner being accused of multiple instances of sexual harassment, was revived in 2020 by two women and native New Orleanians. I was reminded immediately by the “Sugar Heaven and Sugar Hell” map from the atlas that highlighted the wonderful and horrid meanings that simultaneously define this prized commodity: the fuel of slavery and a vital ingredient in the city’s culinary innovations, the root cause of type 2 diabetes and the heart of decadent cultural symbols. A tasteful city staple with a crooked past, Sucré, literally French for sugar, seemed perfectly in place in this discordant history. I took home a box of macarons.

When I returned home, still electric from exploring a place so novel, I decided to read Delia Owens’ Where the Crawdads Sing, which has been adapted into a rather lackluster film, as continued exploration of the coastal part of the South—its warm, lively climate, its murky political history, its cuisine. Kya’s staples, which included grits, hoe cakes, and corn fritters, were not in my vocabulary, and had it not been for my recent move to the United States, I would not have been able to visualize any of those meals. Except for one instance last year, at a hilltop diner in Fredericksburg, I had never seen or eaten grits, and cornmeal is an ingredient you would typically not find in any Filipino kitchen. Where the Crawdads Sing is a memorable, character-driven novel, but the prose walks through the setting so vividly it is hard not to visualize Kya’s kitchen with keen interest. My entire gastronomic experience in New Orleans, which included beignets, cornmeal fried shrimp, seafood gumbo, milk & honey blintz, and chicory coffee, was illuminated by the same curiosity. These dishes introduced me to an America I didn’t really know, one that coexists with fast food burgers, deep dish pizza, Chinese take-out, and Tex-Mex.

What I have learned about this country in the last few months feels surreal as, in many ways, I have known America all my life—gazed at it from a distance, spoke its tongue, read its literature, ate its mass-produced empty calories, lived the consequences of its imperial policies. Being here now feels like seeing a giant so close that it has disappeared.