I spent the last two Sundays of January taking a bookbinding workshop with Austin-based book & print artist Meredith Miller. She runs her print studio Punchpress in the Highlands-North Loop neighborhood where some of my favorite places in Austin happen to be located in: Room Service, the oldest vintage shop in the city, and DrinkWell, where Michael and I had some of the best cocktails in recent memory. Close by, Meredith’s studio shines as another bright dot in my mental map of this beautiful, vibrant area.

Arriving at her studio that first Sunday—nearly an hour late, thanks to road closures from a half marathon I failed to take into account in the commute—I only had the most basic knowledge of bookbinding and a deep love for paper that goes all the way back to my childhood. The studio immediately set me alight. The large, yard-facing window poured the day’s sunlight into the white-painted room, at the center of which was a standing workbench that Meredith and my two classmates were, when I arrived, gathered around. On the walls were beautiful prints and photographs reflecting the sunlight, and on the desk to the far left were stacks of handbound books and a board pinned with smaller prints. At the other side of the room was a letterpress, a cutter, countless labeled metal drawers, and several printmaking machines I don’t even have the vocabulary for. Everywhere was paper.

My embarrassment from being late, excitement for the workshop, and awe at the space combined into a ball of frenetic energy I imagine I barged into the room with. So sorry, thank you for your patience, the studio looks beautiful, I must have said in one breath as I took in everyone’s faces. Meredith with the deep eyes, J— with the bright-cheeked smile, T— with the firm, assuring gaze. I was welcomed with nothing but calm and warmth, and it didn’t take long for me to feel at ease.

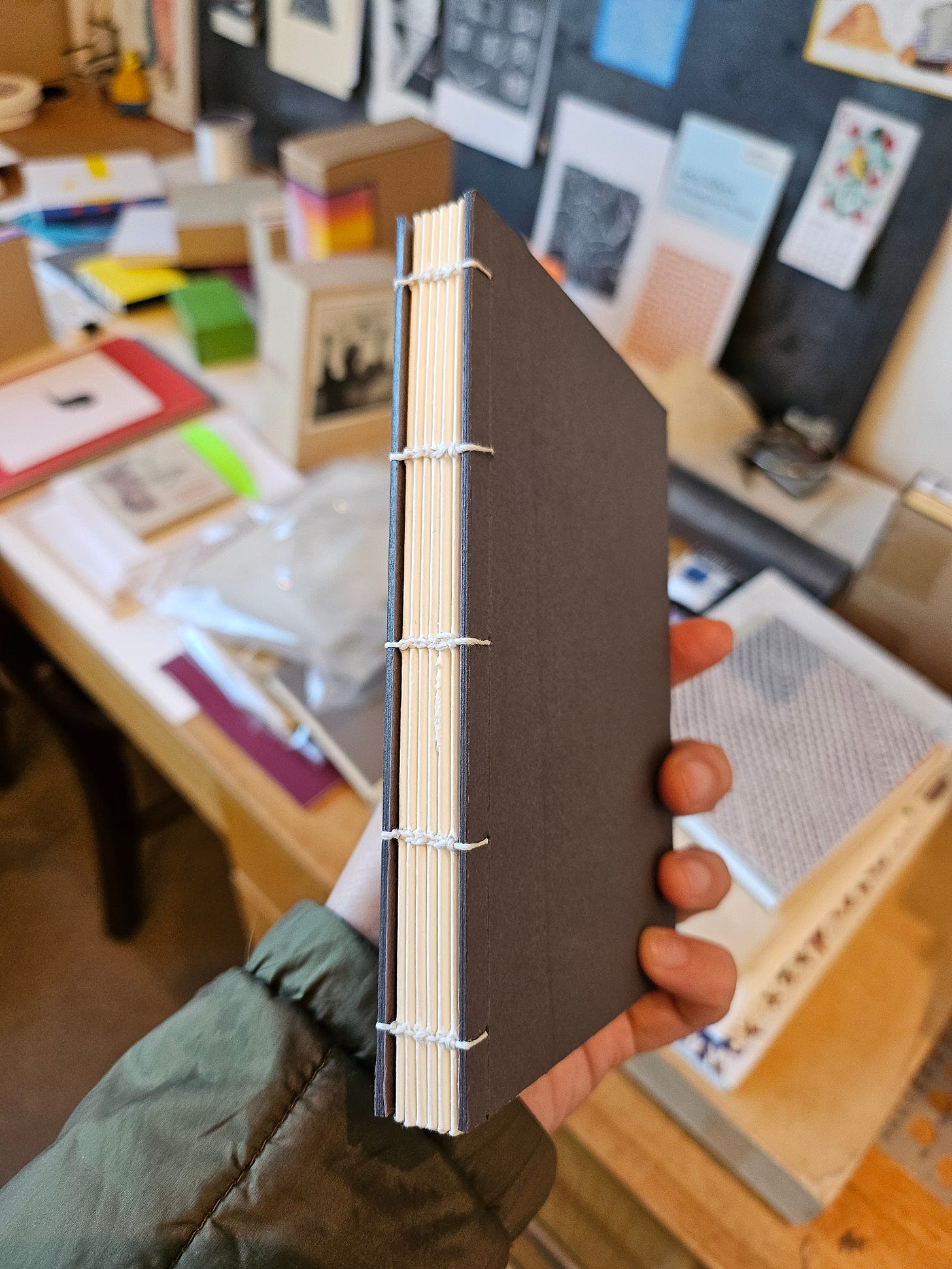

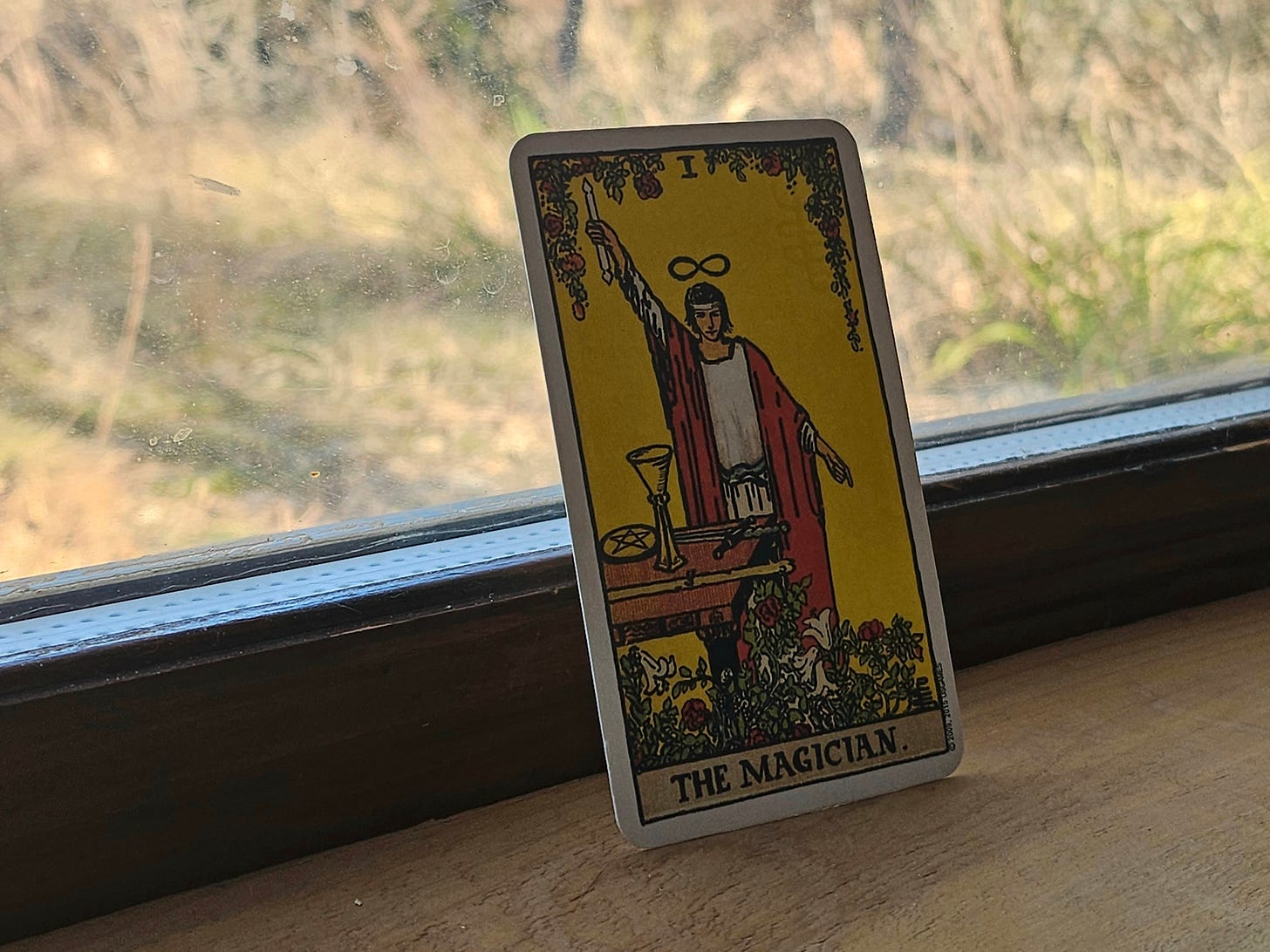

That day we learned two structures: Japanese stab binding and coptic binding. I happen to have done both of these at least once in the past, so admittedly I wasn’t as excited about that session. The restless animal in me was hungry to do something new and now (typical Aries moon impatience). But within the first thirty minutes of the workshop, this animal was quickly tamed and hushed. Yes, these structures were not completely new to me, but the craftsmanship behind them absolutely was. More than a workshop on the craft itself, it was an education on how to hone my body as a force of creation. Transforming materials into something entirely new reminded me of my capacities to make magic. The lessons I took home with me, together with four beautiful handmade books, transcended bookbinding.

Mindfulness is the foundation of mastery

Be mindful, Meredith would often say. When cutting paper with a sharp blade against a metal ruler, one must be mindful. When pulling waxed thread through the holes or sewing stations in the paper, one must be mindful. A lack of attention can lead to injury or damaged materials, especially in such delicate techniques, but I found that every step required the same level of careful thought. Haphazardly folded paper or careless, excessive application of adhesive is obvious in a finished book.

To be mindful is to simply be present. One’s full attention is given to the task at hand, like folding a dozen sheets of paper perfectly in half or conversing with a stranger. It’s different from focus, which I find to be a higher degree of mindfulness. In simply being mindful, I found myself being attuned to my body and its movements. I start to notice the pressure I apply on the ruler when cutting paper, or the mild annoyance when the thread curls around itself while I am sewing. I notice, then adjust accordingly, slowly. I start to press less but with more certainty, or discover a technique with my fingers that guides the thread better through the process. I felt like I was teaching myself, because in learning, say, a gesture, I must learn how to perform it specifically with my body; with the dexterity of my hands, my nervous tendencies, my height, my mental stamina. Attention allows me to meet the world as it is, and as I am.

I imagine that those observations and their corresponding adaptations evolve into muscle memory over time. By then the knowledge, whether it be of bookbinding or of one’s self, sits in the body like a new instinct. Only from there is mastery possible.

A matter of practice

Naturally, the first coptic book I ever bound was wonderfully mediocre. My thread was too thick for the paper, the sewing holes were misaligned, and the covers weren’t perfectly symmetrical. It was truly unappealing to look at, but I was very proud to have turned thread and sheets of paper into a functional notebook that served me well for six months.

Watching Meredith slide a bone folder along the crease of a paper elicited awe. She would be talking us through the procedure, and, seemingly without much thought, her hand would move to and from her torso with a certainty and precision I can only attribute to decades of practice. The friction of the tool on the paper and its clatter on the table as she puts it down made the most satisfying, mechanical sound, like when a gas burner clicks and ignites, and the blue flames whoosh into a circle. It sounded right. How many thousands of times must she have done that exact same gesture to now move with such confidence?

In my hand, the bone folder was not wielded with the same assurance. I had overburnished my paper several times, and in others I had dragged it askew, creating an uneven fold. It was frustrating, but there really is no shortcut to learning a new skill. I just had to do it. The stumbling phase is as necessary as it is inevitable, and after several tries and plenty of patience, I started to find my groove. I could hear the beginnings of music in my movements.

This is true for everything I had ever learned. The first loaf of bread I baked had a burnt bottom, tough crust, dense crumb. My first crochet stitches were too taut. My first published poem was all heart, no craft. That practice matters is not a grand revelation, but even remembering that simple truth seems to require some practice.

Work with what you have

Accessibility was one of the reasons bookbinding, of all the arts to learn, appealed to me. Paper, needle and thread, and scissors are enough to begin learning the craft.

This is also why I also appreciated Meredith’s philosophy on core bookbinding tools. As simple and democratic as possible, she phrased it once. She shared the basics with us, many of which were common, relatively affordable craft supplies like cutters, pencils, and awls, or can easily be built from scrap or cheap materials. Gesturing to the humble set of tools on the table, she said: I’ve made incredible work with just these. Upgrading to expensive tools like laser cutters or a Japanese hole punch is always an option down the line.

Limitation breeds creativity is a cliché I’ve always subscribed to. The inventions made possible by strict poetic forms are great examples. Resourcefulness and innovation stem from limitation, because limitation demands sharp observation. Can I break down shipping boxes to make covers for practice books? What can I make for dinner with just a can of kidney beans, half an onion, and a handful of shiitake mushrooms? How do I create a new outfit with the same wardrobe? I am forced to look around me, to really look, and create with what I am given. There is a vitality around objects that are obviously birthed by an imagination immersed intimately in its environment.

Of course, not all limitations are equal. Leisurely writing a Petrarchan sonnet or making a notebook out of scratch paper is not the same as having only half an hour a day to dedicate to creative endeavors. All of them build the skill, though. Training my eye to rethink the possibilities of what is available—whether it is time, materials, or energy—isn’t just a creative skill; it is also survival.

Know your tradition

It is astounding that in a craft as old as bookbinding, new techniques can still be (re)discovered and created. A key principle in bookbinding, for instance, is folding along the paper grain. But see what happens, she did say, encouraging us to experiment in our own practice and observe the results.

Most of the time, when rules or traditions arrive to us from parents or teachers, they are far removed from the original intention. I personally find it difficult to abide by rules I don’t see the logic of. In this case, folding along the paper grain is a “rule” that ensures a paper folds flat and well. I learned this for the first time during the workshop. Paper tends to crack at the crease or open up if folded against the grain, so it makes sense to follow the best practice. But it isn’t outside the realm of possibility to desire those “unwanted” effects, I imagine. What matters is I understand what paper grain is, why folding parallel to it is considered best practice, and what exactly I’ll achieve if I do it differently.

This was one of the many tidbits of book history I learned during those two Sundays, all of which enriched my understanding of the craft. Embedded in this history are principles of engineering, geometry, and aesthetics, and in learning these I acquired new approaches to problem-solving.

Know the rules before you break them—yet another cliché one must experience to understand.

“It’s just paper.”

If you mess up, don’t stress about it — it’s just paper.

Of all the skills I practiced during the workshop, giving myself the grace to make mistakes was perhaps the most valuable. In my hurry, I accidentally cut paper wrong. I pulled the thread too hard and tore a sheet. My nerves would react as though I made a grave mistake worthy of punishment, but it was literally just paper. Nothing about the world was changed. No one was hurt. The best part is I could either just throw it all away and give up, or try again—either way, nothing would be better or worse.

How I come to terms with the small mistake, however, makes a difference on me. Accidents and moments of failure invite me to exercise my capacity to withstand adversity, bit by bit. They test my resilience, because sometimes, it isn’t just paper. Sometimes it is a car breaking down, or a chronic illness, or accidentally hurting a friend.

They also remind me to remember what is truly important. My book may not be perfect, but in the span of two days I gained new acquaintances, learned new skills, and rekindled my inner creative fire. To begin with, I had the fortune of having the physical, mental, and financial capacity to spend one out of my two days off to drive to Austin, arrive safe, and learn a new art in a stranger’s house.

I left Meredith’s studio feeling alive. Like I could hold stars in my hands.

I am catching my breath after reading this creative exercise and learning again…it’s ok to make mistakes even ones in the creative universe that can’t be taken back but it’s ok! I need to try painting again and accept it is only canvas and it can be painted over😃

I miss my newsletter binding days and when I collected so many trial presses to salvage them later- Now I am salvaging and turning turning turning